Poetry / Marci Vogel

:: « étoiles » ::

. . . trouver bien et mal, bel et lait, sens et folie, et fere son preu de tout par les

examples de l’estoire.

. . . find good and evil, the beautiful and ugly, sense and folly, and profit from all

through the example of history.

Les grandes chroniques de France

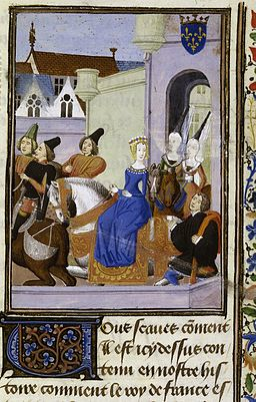

The queen consort enters Paris | August 1389

The queen consort enters Paris | August 1389

The king, seized by madness in the forest of Le Mans | August 1392

The king, seized by madness in the forest of Le Mans | August 1392

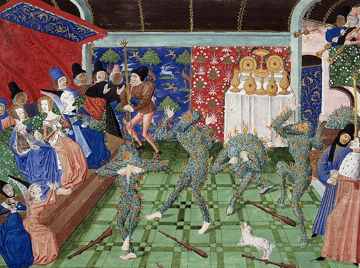

Bal des ardents | January, 1393

Bal des ardents | January, 1393

The Duchess of Orléans leaves Paris | 1396

The Duchess of Orléans leaves Paris | 1396

From the writer

:: Account ::

The unfamiliarity of words allows a certain freedom, and sometimes strange collisions. In Old French, the word estoire means “history,” but it’s also tied to the physical object that conveys the history—the chronicle itself, the narrative source. Estoire can also mean the story of a factual occurrence, which is both tied to time and extends beyond it.

How does our language about any one particular event shift from conveyance to legend, to a story we tell over and over again—like a star, outliving the moment of its birth?

These poems are part of a sequence called « étoiles ». They began as a means of translating a public history and personal story of late medieval poet, Christine de Pizan.

The daughter of an astrologer to Charles V, Christine was widowed at age 25. At that moment the door to our misfortunes was opened, and I, who was still very young, entered. Christine began writing to support herself and her family, engaging in a rigorous course of self-study with the aid of books from the king’s vast library.

As with most life-altering events, my introduction to Christine happened by accident. I was enrolled in a Chaucer course, but my attention kept wandering. One day in the library stacks, I came across a book with brief mention of Christine. Her story so compelled me, I began relearning French after an absence of thirty years so that I might get closer to her poetry.

But poetry, made of language, is not separate from the consciousness of its maker, who exists in a particular place and time in history. And so my wandering continued to unfamiliar waters. As it happens, another definition for estoire is “a fleet of ships,” or an armada. Christine lived in a time of intense historical and political upheaval, and she very intentionally wrote to effect the betterment of a court beset by devastating mental illness and vicious infighting.

The illuminations depicted here, accessed through the digitized collection of the British Library, are from the Chroniques of Jean Froissart, one of the most popular vernacular histories of fourteenth-century England and France. Secular manuscripts such as Froissart’s and the Grandes chroniques de France were typically much larger than devotional books, with lavish narrative illustrations of factual persons, battles, and spectacles. Their audiences included nobles and royals. As Tracey Adams notes, Christine would have relied upon them as an important source for her work.

Charged with brilliant hues, grand pageantry, and dramatic urgency, these centuries-old illuminations relay immediate access to histories inhabited by Christine, and the possibility struck me that our eyes had gazed on the same pictorial stories. Not only the ones in the chronicles, but the ones in the sky.

I began to wonder what shape a poem might take if it were a constellation. How might it tell the story of a young queen? of a king, suffering terrifying incapacity? of tragic entertainments? of a foreign-born noblewoman, unjustly wronged?

In close proximity to the word estoire, my library dictionary lists the Old French word for star: estoile. And if your eye wandered just a bit further, you’d find estoile: see estoire. Which might be translated to mean: History is written in the stars.

Maybe poetry is what illuminates the stories we read there.

Marci Vogel is the author of At the Border of Wilshire & Nobody, winner of the 2015 Howling Bird Press Poetry Prize. Her writing and translations appear or are forthcoming in Plume, Waxwing Literary Review, Brooklyn Rail, Prairie Schooner, and Quarter After Eight. She recently served as a guest commentator for the Jacket2 series, « A poetics of the étrangère » and as a writer-in-residence at Marnay Art Centre in Marnay-sur-Seine, France.