Criticism / Kelly Wisecup

:: Scrapbooking Settler Colonialism: Lists, Hotchkiss Guns, and Temporalities of Violence ::

If you drive as far north as possible on Michigan’s Upper Peninsula, the last town you’ll reach before running out of road and land is Copper Harbor, a small tourist town, population 108. Situated near several eponymous copper mines that saw their heyday in the late nineteenth century and the harbor that connected the region to eastern ports in these moments of economic prosperity, Copper Harbor now relies on this past for its sense of identity. A set of painted wooden planters welcomes visitors to the town, proclaiming that this is “Where History Begins” and placing the town’s origins in 1843 (Fig. 1). This beginning is placed conveniently after copper was “discovered” by white men in 1840 and after the 1842 Treaty of La Pointe, in which Ojibwe nations ceded land in what are now called the Keweenaw Peninsula, Minnesota, and Michigan to the United States. [i] Copper Harbor’s welcoming planters and local history create a temporal rift that allows time to begin at a moment that emphasizes “pioneers” and their excavation of mineral resources. The story is one of resourcefulness, mining booms and busts, lighthouses, shipwrecks, forts, and mines. It’s also a story that some residents posit as explicitly at odds with Indigenous histories of the peninsula. A local tour guide insisted to our group, in response to one woman’s comment that Native people were the first “Americans,” that “our” history was pioneer (aka white) history and that it was important to the region to preserve that story. Copper Harbor’s history is aimed at making white settlers (like me) feel comfortable with the existing way of things and at assuring everyone of the continued viability of these histories and ways of life.

Fig. 1. Cooper Harbor. Photo by the author.

Native people are not wholly absent from the town’s histories, however: a small museum attached to the Minnetonka Resort advertises “Indian Relics.” These “relics” are held in a room packed with other unrelated objects: photos, antiques, old toys, an early diving suit, and family memorabilia. The back wall is devoted to cases holding the promised “relics”: the cases are filled with arrowheads, knives, and other tools that “man” employed for “war and domestic use,” materials that white settlers collected from the fields and beaches they claimed as theirs. One particularly macabre case arranges beaded bags, dolls, and collectible cards featuring Native leaders alongside an unidentified skull (Fig. 2). This case mixes domestic and artistic materials with items created specifically for collecting and circulating, in this way framing the dolls and bags—items made for play and for practical use—as the equivalents of the collectibles. Placed in the context of the case, the dolls and bags are disconnected from the people who made and used them; the exhibit transforms them into objects for display, the possessions of white settlers keen to contain the peninsula’s Indigenous histories and futures in museums.

Fig. 2. “Relics.” Photo by the author.

This image has been cropped to show only the cards and dolls, as an acknowledgment of the ongoing trauma produced both by local collections like the one in Copper Harbor and by more visible museum displays that feature human remains and other Indigenous materials. The 1990 Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA) required federally funded repositories to identify the lineal descendants and tribal communities to which Native American cultural items belong and to return such items. However, non-federally funded museums such as the one run by the Minnetonka Resort are not covered by the law and are thus not legally required to repatriate human remains and other materials.

Meanwhile, the unidentified skull stands as a claim to Indian vanishing and even perhaps as a threat to the imagined future for Native peoples that the dolls—the possessions of a new generation—symbolize. Placing the skull in proximity to the dolls, the case suggests that all of the objects are the materials of a dead and vanished people while also erasing histories of Indigenous removal and of persistence (the latter belied by a photograph across the room of a “halfbreed Chippewa” woman who lived in Copper Harbor). The placement of the cards, human remains, and dolls in a single case points not only to the nineteenth-century fondness for arranging items in eclectic configurations but also to the ways that settler colonial history rests on collapsing object distinctions and temporal categories in order to tell its stories. The frame of the case generates relationships among these materials that otherwise might not exist, using spatial proximity to create a story of death, disappearance, and settler possession. Rather than establishing relations across histories that might prompt settlers and other viewers to attend to pre-existing and ongoing Indigenous histories, the move to conflation and collapse acts as a vehicle of erasure. [ii] The museum (and the town) need not acknowledge their dispossession of the Ojibwe people whose homelands they settled, nor the continued presence and influence of Ojibwe communities in the area. [iii]

The museum of Indian relics, the claims that Copper Harbor is “where history begins,” the insistence that pre-existing and alternate histories threaten settler colonial ones: these are nothing new. [iv] If anything, Copper Harbor’s narratives are simply a more explicit than usual articulation of the connections between histories of vanishing Indians and national progress that continue to dominate US American statements about Native people. But as I write this in this summer of making America “great again” with proposals for border walls and bans to prevent Muslims from entering the US; of black men killed by police in Chicago, Milwaukee, Baton Rouge, and Minneapolis; of Indigenous men and women killed in Saskatchewan and Albuquerque; and of news reports designating Standing Rock Sioux people protesting a pipeline on their reservation as “occupiers” of their own lands, Copper Harbor’s ongoing insistence on settler histories cannot be seen as just a nineteenth-century throwback. [v] Instead, the town’s histories participate in an ongoing mode of visualizing time and belonging that continues to feed contemporary structures of violence. This structure depends, just as it did in the nineteenth century, on settlers’ claim to be able to choose their own origins and to disconnect history from dispossession and from violence against Indigenous peoples and other people of color to preserve and justify settler privileges.

In one response to the events of this summer, activists have deployed social media as a tool for organizing and for broadly exposing just how frequent, linked, and ongoing this violence is. Both Black Lives Matter and Idle No More—some of the most visible movements protesting violence against people of color and settler colonialism—spread news of their protests quickly and widely using Twitter. [vi] But the use of media to respond to colonialist violence isn’t new either: the activist uses to which Twitter, Facebook, and Instagram feeds have been put have a forerunner in a set of nineteenth-century scrapbooks compiled by a Seneca man named Ely S. Parker.

A scrapbook might seem an unusual material object to compare with social media. But scrapbooks and social media alike present information by accumulating and stacking excerpts or clips in a central location that users can access in multiple ways: linearly, by reading the scrapbook from beginning to end, or scrolling through a Facebook feed; nonlinearly, by reading around in the scrapbook or on the feed; or by using a particular excerpt as a platform out of the page to explore a topic in depth. Like Facebook and Twitter, scrapbooks are, formally, lists: they do not necessarily generate their own content but have as a key function their ability to arrange entries and objects next to one another. These media are nonsyntactic, not oriented by time. Instead, they posit a non-narrative temporality that links the different months or days or weeks in which an event took place, compressing the space and time between them.

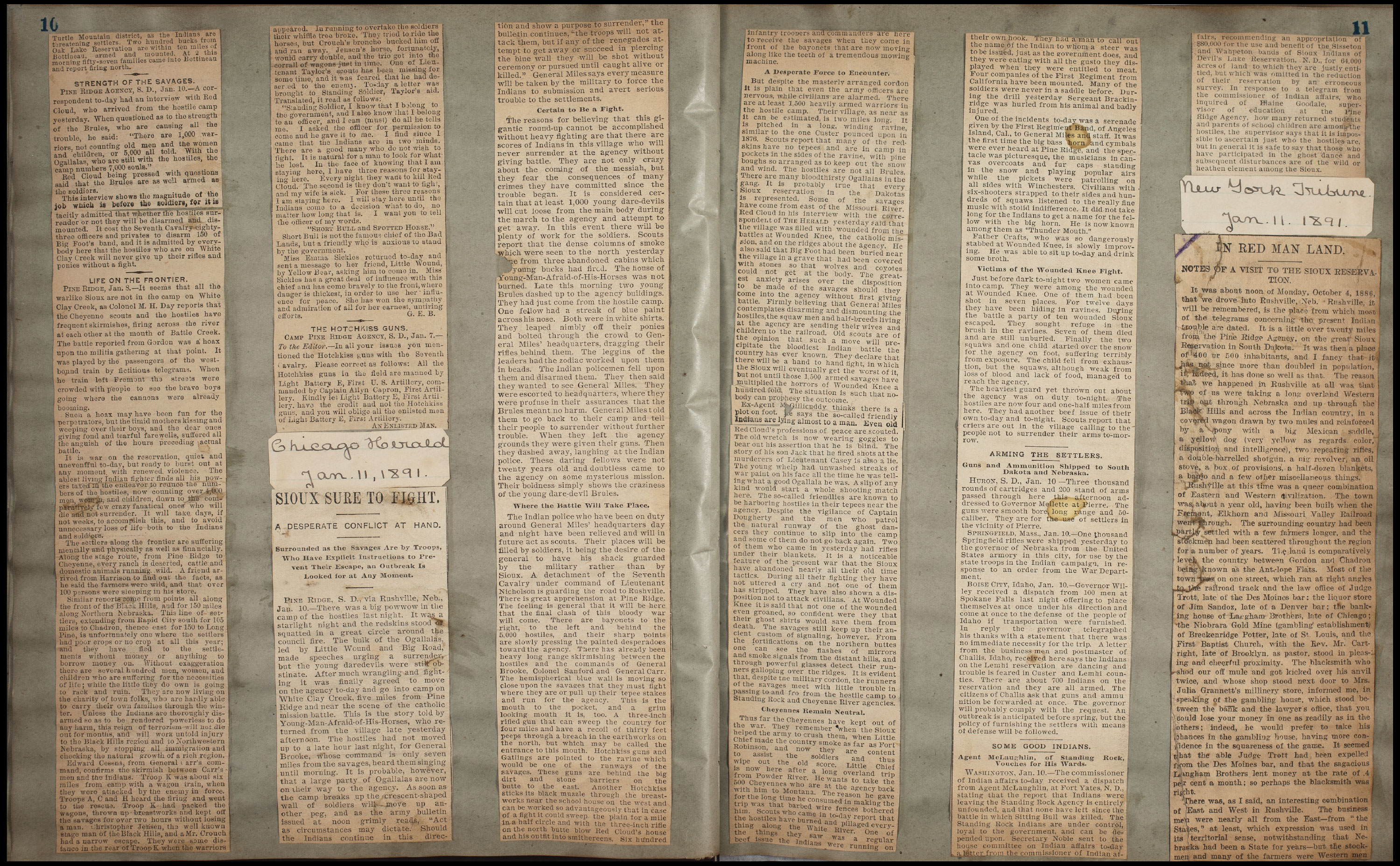

In 1891, Ely S. Parker, an adjutant to General Ulysses S. Grant during the Civil War and the first Native Commissioner of Indian Affairs in Grant’s administration (a post comparable to the contemporary position of Assistant Secretary of Indian Affairs), collected and arranged newspaper reports of the Wounded Knee Massacre. [vii] On December 29, 1890, U.S. soldiers killed between 150–300 Lakota men, women, and children who had camped with their leader Big Foot near Wounded Knee Creek under a white flag. News reports manufacturing salacious accounts of an imminent threat by “Sioux hostiles” circulated through reporters who had accompanied soldiers to Pine Ridge Agency, on Lakota lands within the newly minted state of South Dakota, where they had been sent to put down an alleged uprising (Fig. 3). Drawing from multiple newspapers, mostly published in Chicago, Parker excerpted and pasted these stories into a Mark Twain Scrapbook, a hefty bound book with printed page numbers and blanks for an index, as well as pages pre-treated with adhesives. Parker includes no rationale for his selection and arrangement of news clippings, but the Wounded Knee Massacre was the subject of only one of his twelve scrapbooks, now held at the Newberry Library in Chicago. He collected thousands of newspaper articles about Native Americans, ranging from images of the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition and local antiquarians’ self-satisfied tours of Plymouth Rock to smug notices regarding Dakota writer and physician Charles Eastman’s marriage to the US American poet Elaine Goodale.

Fig. 3. Ely Samuel Parker scrapbooks. Photo Courtesy of The Newberry Library, Chicago. Call # Ayer MMS Parker, Scrapbook 6.

When read successively, the scrapbooks produce a tally of popular, often racist stereotypes of Native people that circulated in the media. Parker’s scrapbooks represent the American public’s fascination with what one paper termed “Aboriginal Fragments”: stories and accounts of Native life, material culture, and history. [viii] In this way, the scrapbooks might seem to reflect their participation in and documentation of what Brian Hochman has called the “ethnographic origins of modern media technology.” [ix] Focusing on the photograph and phonograph, among other technologies, Hochman argues that our contemporary media have their origins in salvage ethnography and in US Americans’ conviction that Native peoples’ lives needed to be recorded before they vanished. Technologies like the camera, sign language, and phonograph, among others, claimed to protect Native people from time by isolating them in a particular historical moment. [x] Indeed, Parker collected news stories in a context in which artists, ethnologists, antiquarians, farmers, local boosters, and others found it both exciting and the most natural thing in the world to collect arrowheads from one’s field, travel throughout North America to paint or to photograph Native people, or place human remains, dolls, and beaded purses next to one another in a small Midwestern museum.

But Parker’s scrapbooks, as antiquated and analogue as their pages might seem in comparison to smart phones and social media sites, offer conceptualizations of time and of colonialism’s materials that contest the narratives of Indigenous vanishing and settler innocence circulated in both the nineteenth-century and our own moment. Parker’s scrapbooks intervene in the “ethnographic” work of modern media by positing time as something one can manipulate. As he selects and arranges images, flips through the book in a nonlinear fashion, Parker (and other readers) make their own path through history, even a history circumscribed by the popular media and discourses of vanishing. [xi] Or, should one take a linear route through scrapbook 6, the accounts of tensions at Pine Ridge Agency accumulate as one turns the page, with clippings from Chicago newspapers reporting “hostiles” coming in to surrender, “hostiles within range,” “Sioux sure to fight,” and a series of headlines suggesting that the “Sioux” were deliberating whether to fight or surrender.

In the middle of these reports from Wounded Knee, Parker pastes a long article about the Hotchkiss gun (Fig. 4). He arranges descriptions and illustrations of the “modern instruments of war” over four pages which detail the gun’s technological capabilities: its accuracy, its ability to throw “explosive shells,” and ultimately, its success convincing Ghost Dancers that they were not protected from the US Army’s bullets. The article details the gun’s ammunition, compares it to the Gatlin gun, and comments on potential accidents involved in operating the gun. It also notes that Chicagoans narrowly missed seeing its power in “sweeping away a mob at the time of the Haymarket riot.” [xii]

Fig. 4. Ely Samuel Parker scrapbooks. Photo Courtesy of The Newberry Library, Chicago. Call # Ayer MMS Parker, Scrapbook 6.

When the firing started at Wounded Knee, it wasn’t just rifles killing Big Foot and his people but also four Hochkiss guns with their explosive shells and vaunted accuracy. The four scrapbook pages detailing the gun’s technology, inner parts, and ammunition intervene in the building pace of reports of Lakota “hostilities.” Parker pauses—and makes his readers pause too—before articles titled “It’s a Real Surrender” and “Hostiles in a Panic” and before reports and illustrations of the massacre to think about a gun and its capabilities, its effect on the bodies of Lakota children, elderly people, and men and women. The four pages devoted to the gun take hold of time, slow it down, ask readers to live in the moment between uncertainty and massacre. The pages urge readers to stop amid the onslaught of settler colonial anxiety about “hostiles” on which the papers focus and to think instead, as Parker must have, about Lakota families in the middle of a cold winter on their way to Pine Ridge Agency for protection and of the four Hotchkiss guns on the hill above Big Foot’s camp.

Because lists are not narrative, they’ve been the sort of object that literary scholars often disregard for allegedly more “literary” texts and that historians often admire for their supposed ability to get close to the past. But Parker’s scrapbooks suggest that textual and material lists are more complicated than descriptions of them as non-literary or as documentary evidence might indicate. Lists, like Parker’s scrapbooks, make no promises to tell a story or to resolve conflict; instead, they sort, arrange, and order information on the material space of the page. “Lists do not communicate,” as Cornelia Vismann argues, “they control transfer operations”; they “sort and engender circulation.” [xiii] Focusing on these qualities, scholars have viewed lists as a key transition between orality and literacy, marking their appearance as a culture’s early turn toward the permanency and stability of writing. [xiv] Yet Vismann argues that the list’s ability to circulate information links it not to the oral-literacy binary but to administration and thus to law. Creating lists, Vismann argues, legitimizes and authorizes the state by producing a material object that stands as a site of regulation, administration, and power. [xv] Moreover, because lists and the files they create both communicate and document an act—“writing up while writing along”—they take on a reputation as objects that can relate the past without the obfuscation and deception of narrative. [xvi] Files offer information not only about an event but also about the extraneous happenings, speeches, documents, and so on that led up to that event. They seem to “captur[e] the immediacy of speech acts and other acts.” [xvii]

By performing the acts of sorting, filing, and managing characteristic of lists, Parker’s scrapbooks create an expansive record or file of US stories about Native Americans and specifically about Wounded Knee. However, they establish a very different relation to the past and to power than the one Vismann theorizes. Rather than claiming to record and order the past, Parker’s scrapbooks expose how history is created through the circulation of news reports and their repetition of fears about “hostiles” or claims about Indian vanishing. His lists also go beyond “controlling transfer operations” or circulating information. [xviii] Instead, scrapbook 6 offers an alternate, material space in which to grapple with the massacre at Wounded Knee, one that exists alongside and at times in tension with the spaces of the reservation, of Wounded Knee Creek, of a world’s fair, of boarding schools. This alternate space rewrites dominant histories by locating alternate causes for events and imagining alternate futures. Such futures are by no means utopian, as Parker’s Hotchkiss interlude shows; instead, they more often excavate US military and colonial violence that reporters erased from accounts of Wounded Knee. [xix] The scrapbooks also connect seemingly unrelated acts of violence: the Hotchkiss gun becomes a link between the Wounded Knee massacre and the Haymarket affair; it relates Potawatomi and Lakota lands (or what newspapers called Chicago and South Dakota), police and military violence against labor protesters and Lakota families. Parker’s scrapbooks offer no answer to this violence, but they also provide no excuse to turn away. If anything, they ask readers to linger on these moments of violence, to consider the justifications by which it is perpetuated. It’s this lingering, this moment when you realize that you’ve been reading about a Hotchkiss gun for four pages, that makes it impossible to read the successive reports of the massacre as an isolated incident or as the consequence of actions by “hostile” Lakota peoples. The scrapbook opens up spaces of relation in the dominant history told by newspapers, and in doing so, it intervenes in the linear time of the modern nation state, remapping historical and spatial relations among people and places claimed by the US and reconnecting stories of violence, dispossession, and nation building.

Against the stories of certain death and vanishing that the display cases in Copper Harbor and news reports of Wounded Knee aim to produce, activist uses of non-narrative forms like lists and social media feeds disrupt the timelines that the US and other nation states create to dislocate the present from histories of colonialism, dispossession, and racism. Crucially, this disruption is located not only in the pages of scrapbooks or on digital sites but also in readers’ and users’ interaction with these sites. Readers of Parker’s scrapbooks speed up and scramble time by linking the invention and use of Hotchkiss guns with the massacre at Wounded Knee and the Haymarket riot, in this way complicating narratives of violent Lakota men and certain US dominance. This summer, in response to activism and protests, the Chicago Police Department moved quickly to release footage showing a police shooting of an unarmed black teenager, in effect speeding up the time of reporting and accountability. [xx] The Dakota and other tribes currently protesting the Dakota Access Pipeline’s planned route through the Standing Rock Sioux Reservation interrupt oil companies’ timelines of extraction and production, while the Twitter and Facebook stories about the protest disrupted and contested the news cycles from which accounts of the protest remained largely absent for months. [xxi] These varying temporal arrangements not only emerge out of literary forms and technologies that circulate information, they also offer possibilities for revising that information to account for the violence on which North American settler histories rest.

[i] This treaty contained provisions allowing the signatories to continue to use the ceded lands for certain purposes, but the state and federal government generally ignored these provisions.

[ii] Indigenous histories of the Upper Peninsula long preceded settler ones, often circulating in oral forms or being recorded on materials like copper plates. See William W. Warren, History of the Ojibway People (first published 1885, Minneapolis: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 2009), 53. Moreover, several Ojibwe men published written histories of their people after the Treaty of La Pointe in which they clearly contradict Copper Harbor’s claim that history began in 1843. See Warren, George Copway, The Traditional History and Characteristic Sketches of the Ojibway Nation (London, 1850), and Andrew J. Blackbird, History of the Ottawa and Chippewa Indians of Michigan (Ypsilanti, MI: 1887).

[iii] There are multiple signs of this presence and influence: Keweenaw Bay Indian Community is located an hour and a half from Copper Harbor (http://www.kbic-nsn.gov); the local NPR station features regular news segments about the Community. Readers of The Account may also be especially interested in the poetry of Shirley Brozzo, a poet from the Keweenaw Bay Indian Community. See Brozzo, “Circle of Life,” in Traces in Blood, Bone, and Stone: Contemporary Ojibwe Poetry, ed. Kimberly Blaeser (Bemidji, MN: Loonfeather Press, 2011), 37.

[iv] For one study of such narratives, see Jodi Byrd, The Transit of Empire: Indigenous Critiques of Colonialism (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2011).

[v] Jack Healy, “Occupying the Prairie: Tensions Rise as Tribes Move to Block a Pipeline,” New York Times 23 Aug. 2016, http://www.nytimes.com/2016/08/24/us/occupying-the-prairie-tensions-rise-as-tribes-move-to-block-a-pipeline.html?_r=0.

[vi] For coverage of some of these activist uses of social media, see Bijan Stephens, “Social Media Helps Black Lives Matter Fight the Power,” Wired (Nov. 2015), http://www.wired.com/2015/10/how-black-lives-matter-uses-social-media-to-fight-the-power/; Elizabeth Day, “#BlackLivesMatter: the birth of a new civil rights movement,” The Guardian 19 July 2015, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2015/jul/19/blacklivesmatter-birth-civil-rights-movement; and Shari Narine Sweetgrass, “Social media major driver in Idle No More movement,” Aboriginal Multi-Media Society 30, no. 11 (2013), http://www.ammsa.com/publications/windspeaker/social-media-major-driver-idle-no-more-movement.

[vii] Parker was the first Native American Commissioner of Indian Affairs; he worked throughout his tenure in the position to reform federal Indian policy, especially by insisting that the US honor its treaties. For an excellent study of Parker’s work, see C. Joseph Genetin-Pilawa, Crooked Paths to Allotment: The Fight Over Federal Indian Policy After The Civil War (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2012).

[viii] Ely Samuel Parker scrapbooks, scrapbook 6, Edward E. Ayer Collection. The Newberry Library, Chicago, IL.

[ix] Brian Hochman, Savage Preservation: The Ethnographic Origins of Modern Media Technology (Minneapolis, University of Minneapolis Press, 2014).

[x] Ibid., xvi.

[xi] On scrapbooks’ ability to offer alternate histories, see Nicole Tonkovich, The Allotment Plot: Alice C. Fletcher, E. Jane Gay, and Nez Perce Survivance (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2012).

[xii] Sunday Inter Ocean, 18 Jan. 1891, 9.

[xiii] Cornelia Vismann, Files: Law and Media Technology, trans. Geoffrey Winthrop-Young (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2008), 6. As Ellen Gruber Garvey has pointed out, nineteenth-century newspaper clipping scrapbooks offered a form of “active reading” that made white middle class readers into agents who could change the meaning of their “saved items” (47). Scrapbooks allowed readers to “save, manage, and reprocess information” (6), acting as “filing systems” that recorded how people read (4). See Ellen Gruber Garvey, Writing With Scissors: American Scrapbooks from the Civil War to the Harlem Renaissance (New York: Oxford University Press, 2013). See also James Delbourgo and Staffan Müller-Wille, “Introduction,” Isis 103, no. 4 (2012): 713, who comment that lists “inventoried and organized the accumulated world.”

[xiv] See Walter J. Ong, Orality and Literacy: The Technologizing of the Word (New York: Routledge, 2012), chap. 4.

[xv] Vismann, xii.

[xvi] Ibid., 8.

[xvii] Ibid., 9.

[xviii] Ibid., 6.

[xix] Likewise, for all their activist uses, social media have also been the sites of harassment and much racist, xenophobic, and sexist commentary. Their possibility as activist tools is, like Parker’s scrapbooks’ relation to newspapers, always in conflict with ongoing settler colonial and racist narratives and histories. On the ways that digital media reproduce colonialist terms and relations to Native Americans, see Jodi A. Byrd, “Digital 2.0: Digital Natives, Political Players, and the Power of Stories,” Studies in American Indian Literature 26, no. 2 (2014): 55–64.

[xx] See Annie Sweeney, Jeremy Gorner, and Alexandra Chachkevitch, “Videos capture dramatic police shootout with carjacking suspect,” Chicago Tribune 18 Aug. 2016, http://www.chicagotribune.com/news/local/breaking/ct-chicago-police-officer-shot-video-met-20160817-story.html.

[xxi] See the hashtag #noDAPL for example.

Bibliography

Blackbird, Andrew J. History of the Ottawa and Chippewa Indians of Michigan. Ypsilanti, MI: 1887.

Brozzo, Shirley. “Circle of Life.” In Traces in Blood, Bone, and Stone: Contemporary Ojibwe Poetry. Edited by Kimberly Blaeser, 37. Bemidji, MN: Loonfeather Press, 2011.

Byrd, Jodi A. Digital 2.0: Digital Natives, Political Players, and the Power of Stories,” Studies in American Indian Literature 26, no. 2 (2014): 55–64.

—. The Transit of Empire: Indigenous Critiques of Colonialism. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2011.

Copway, George. The Traditional History and Characteristic Sketches of the Ojibway Nation. London, 1850.

Day, Elizabeth. “#BlackLivesMatter: the birth of a new civil rights movement.” The Guardian, 19 July 2015. Accessed September 1, 2016. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2015/jul/19/blacklivesmatter-birth-civil-rights-movement.

Delbourgo, James and Staffan Müller-Wille. “Introduction.” Isis Focus: Listmania 103, no. 4 (2012): 710–15.

Garvey, Ellen Gruber. Writing With Scissors: American Scrapbooks from the Civil War to the Harlem Renaissance. New York: Oxford University Press, 2013.

Genetin-Pilawa, C. Joseph. Crooked Paths to Allotment: The Fight Over Federal Indian Policy After The Civil War. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2012.

Healy, Jack. “Occupying the Prairie: Tensions Rise as Tribes Move to Block a Pipeline,” New York Times 23 Aug. 2016. Accessed September 1, 2016.

http://www.nytimes.com/2016/08/24/us/occupying-the-prairie-tensions-rise-as-tribes-move-to-block-a-pipeline.html?_r=0.

Hochman, Brian. Savage Preservation: The Ethnographic Origins of Modern Media Technology. Minneapolis: University of Minneapolis Press, 2014.

Ong, Walter J. Orality and Literacy: The Technologizing of the Word. New York: Routledge, 2012.

Parker, Ely Samuel. Scrapbook 6. Edward E. Ayer Collection. The Newberry Library, Chicago, IL.

Stephens, Bijan. “Social Media Helps Black Lives Matter Fight the Power,” Wired (Nov. 2015). Accessed September 1, 2016. http://www.wired.com/2015/10/how-black-lives-matter-uses-social-media-to-fight-the-power/.

Sunday Inter Ocean, 18 Jan. 1891.

Sweeney, Annie, Jeremy Gorner, and Alexandra Chachkevitch. “Videos capture dramatic police shootout with carjacking suspect.” Chicago Tribune 18 Aug. 2016. Accessed September 1, 2016. http://www.chicagotribune.com/news/local/breaking/ct-chicago-police-officershot-video-met-20160817-story.html.

Sweetgrass, Shari Narine. “Social media major driver in Idle No More movement.” Aboriginal Multi-Media Society 30, no. 11 (2013). Accessed September 1, 2016. http://www.ammsa.com/publications/windspeaker/social-media-major-driver-idle-no-more-movement.

Tonkovich, Nicole. The Allotment Plot: Alice C. Fletcher, E. Jane Gay, and Nez Perce Survivance. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2012.

Vismann, Cornelia. Files: Law and Media Technology. Translated by Geoffrey Winthrop Young. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2008.

Warren, William W. History of the Ojibway People. 1885. Minneapolis: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 2009.

Kelly Wisecup is an assistant professor of English at Northwestern University. She is at work on a book called Assembled Relations: Collection, Compilation, and Native American Writing, about the strategies with which eighteenth- and nineteenth-century Native American writers intervened in colonial collecting projects. She is the author of Medical Encounters: Knowledge and Identity in Early American Literatures (University of Massachusetts Press, 2013) and essays in The Native American and Indigenous Studies Journal, Early American Literature, Early American Studies, and Atlantic Studies.

Sarah Sillin, Guest Criticism Editor, received her Ph.D. from the University of Maryland and is currently a visiting assistant professor of American literature at Gettysburg College. Her book project, entitled Global Sympathy: Representing Nineteenth-Century Americans’ Foreign Relations, explores how writers envisioned early Americans’ ties to the larger world through their depictions of friendship and kinship. Sillin’s essays have appeared in Multi-Ethnic Literature of the United States and Literature of the Early American Republic.