Fiction / Monica Kim

:: What the Crow Knows ::

We found the dead crow before my older sister got into David Moon’s car but after the power went out.

We didn’t know why the power went out, and if we did know, I don’t remember now. It’s been ten years since that day. My sister once claimed it was because of all the electronics running at the same time, competing with the heat—the aircon, the GameCube, the desktop computer where she was messaging David Moon on AIM—though she didn’t tell me this last fact until now. Andrew, at the time, said it was because of the apartment complexes we all lived in, since everyone else’s power went out too. And Henry, of course, said he didn’t care what caused the power outage, he just wanted to find something to damn do. His voice cracked at the word damn, and he looked around the room as if his parents were there to gasp and pray over the words of an eleven-year-old boy. All I know is that we were playing Mario Kart on Andrew’s GameCube, with Andrew in third, Henry in sixth, and me in eleventh, and just as I’d gotten an item box with a black bullet to rush past everyone else, the game cut and the television turned black.

We groaned. Henry threw his controller onto the ground, even though it wasn’t his. Andrew got up and started shaking the small square television, then kicked the GameCube, which he could do, since it was his and he was the only one of us who owned one. I stretched my arms above my head, feeling the sweat already start to bead on the back of my neck.

It was sometime in early June, a day that felt unusually like the middle of July, and we complained about the aircon that was now suddenly shut off. Andrew scrounged around the living room and found the delicate paper fans his mom brought from Korea and kept tucked away in a wooden box underneath the faded tan couch. We slumped onto the floor, fanning ourselves with the pink and red and white fans lined with hangul and hanja calligraphy.

“What do we do now,” Henry whined, flicking the controller’s buttons uselessly.

“Caleb,” Andrew said, turning to me, fanning himself so furiously I thought his wrist might fall off. “Ask your noona what to do.”

It was an unarticulated fact that Andrew was our ringleader. It wasn’t just that Andrew’s family had more money than mine and Henry’s, that he was an only child, that he seemed to have friends outside the two of us, whereas Henry was pretty much indifferent to most people he met and I was too tongue-tied to ever start a conversation with anyone. It was also that Andrew had a face most people, children and adults alike, but especially me, couldn’t say no to: uneven bangs that somehow endeared him to everyone despite every other Korean American boy having the same haircut, the small dimple on his left cheek that widened when he smiled.

“Okay,” I said, getting up and walking to Andrew’s parents’ room, where the shared desktop computer was. My older sister, Jennie, was sitting at the desk, elbows on the wood-worn table. In front of her was the black screen of the dead computer and her sketchbook with a new drawing I couldn’t see.

All of our parents worked and figured having Jennie babysit the three of us was much more ideal than enrolling us in the only after-school program that catered to Korean Americans in this tiny town. So, Jennie often sat at this computer, sketchbook nearby, probably wishing she was with her friends doing whatever fourteen-year-old girls did. But instead, she was stuck looking after her younger brother and his two idiot friends. Sometimes she bribed us with some of her babysitting money and left us by ourselves, making us swear that if we didn’t tell our parents she was going off to watch the high school soccer game because David Moon was playing, she’d let us have fifteen bucks to order BonChon Chicken or buy Pokémon cards or whatever else nerds like us did these days. Andrew would merely raise an eyebrow, asking why we shouldn’t just take her money and tell our parents anyways, while Henry would widen his stance and cross his arms, and I’d look at my sister with her hair curled and black eyeliner smudged around her eyes and wonder what happened to the girl who used to play GameCube with us.

Because you’ll get the GameCube taken away if you tell, she’d say to us, mostly to Andrew, and then leave, tucking however many bills she had into my palm.

“Noona?” I asked, and she turned around, still holding her pencil. “The power’s out. What do we do?”

She looked out the window; we both startled as a bird flew past, a black blur against the clear pane.

“I don’t know, go outside or something.” She waved a hand dismissively, and made to turn back around, when I stepped forward.

“But what would we do outside? It’s too hot to play Manhunt or pretend to be Naruto characters or anything.”

My older sister rolled her eyes. “Well, duh. I don’t know, find a card game or board game or whatever.”

She began to turn again, when I tugged on her ponytail.

“Caleb‑a,” she hissed, using the Korean pronunciation of my name, which meant that she was really, really annoyed with me.

“Noona,” I said, crossing my arms, trying to copy Andrew. “If you hang out with us, I promise I’ll leave you alone for the rest of the week.”

She closed her eyes, resting her fingertips on her temple. She looked like our mom in that moment, when Jennie and I would fight over who should set the table for dinner. Why can’t Caleb do it for once, omma? Jennie would ask. Why does it always have to be the girl?

Jennie opened her eyes, glancing at the window, and I wondered if she was waiting for something. Maybe another bird to fly by.

“Fine,” she finally said, taking one last look at the dead computer before standing up. She ripped a page she was working on from her sketchbook, then shoved it into her shorts pocket. “But this is gonna take twenty minutes, tops.”

~

We brought our fans with us outside, swapping hot air for hot air.

“Aren’t you afraid someone will see us with these?” Henry asked, as Jennie closed and locked the door behind us. “They look kinda girly.”

Andrew continued to fan himself. “Do you wanna be super hot without one?”

Henry grumbled something but didn’t say anything more. Andrew’s word was Andrew’s word.

Jennie shielded her eyes with a hand. “Alright, where to?” She didn’t look at anyone when she asked this, but we all knew she was talking to Andrew.

He shrugged. “We can just walk around.”

Jennie sighed but led the way, walking a few paces ahead of us, as if she couldn’t wait to be rid of us—which was probably, most definitely true.

There isn’t much of the walk I remember, because we’d walked around the neighborhood probably hundreds of times, scoping out the best places to hide for Manhunt, the best patch of grass to kick a soccer ball back and forth, the best stretch of asphalt for races. I don’t know if the images stored in my head from this day’s walk are a collection of images patched together into a mismatched kaleidoscope, or if their source is truly from this odd early June day. But Jennie tells me these are the images she remembers, or at least the ones she draws, when she finds herself obsessively replaying the day’s events, unable to cut herself from the loop: the three of us, Andrew, Henry, and I, kicking tiny dislodged chunks of asphalt against the backs of her bare legs—the open doors of neighbors’ apartment-houses—a glimpse of furniture, the tattered floral ottoman with a rip on the seam, perhaps from a cat, perhaps from something else—up a set of neutral gray concrete stairs, no railing, to more lookalike apartment-houses—the same faded yellow, faded tan, faded blue—cutting across someone’s grass—running when we heard a dog bark—down a different set of neutral gray concrete stairs, returning a different, backward way to Andrew’s place—coming across the dead crow splayed at the foot of the black dumpster.

Everyone remembers finding the crow in a different place. Jennie says it was at the foot of the black dumpster. Henry told me, earlier today––before I talked to Jennie––that it was on Andrew’s doorstep. What Andrew remembers, I don’t know, because I haven’t talked to him in years. I don’t know if this is a blip in his memory, if he thinks about this day as much as Jennie does and I now do, or if he doesn’t remember it at all, if it’s like the day never existed for him.

But this I know for sure: we all remember who touched the crow.

~

It wasn’t the first time I’d seen a dead animal. Roadkill was common on these suburban roads. But there was something about this crow—its bent wing, its bloodlessness, the open eye—that unnerved me.

“I don’t like this,” Henry muttered, even as Andrew bent down.

“Hey,” Jennie said sharply, and Andrew’s head snapped in her direction. “It might have the plague.”

“I thought that was a long time ago,” he replied.

“It was,” she agreed, arms now around herself, as if she was cold. “But that doesn’t mean it isn’t cursed or anything.” She looked at me, and I knew what she was thinking.

The crow had to be a bad omen. Koreans are, if not anything else, very superstitious people, and Jennie and I were no exception. We made sure all the doors were closed at night. We never turned the fan on while we were sleeping, not even in the summer months. When we had a bad dream, we made sure to wait at least twenty-four hours before telling all the details to our mom, and if we had a good dream, we made sure to tell her right away. We made sure our beds in the room we shared weren’t facing the door. Even to this day, when I catch myself whistling at night, I’ll stop, afraid of seeing the deathly spirit my mom said would surely come, whom I always imagined as a kind of ghost girl version of Jennie, long black hair hanging in front of her face like a curtain.

“Well, we can’t just leave it here,” Andrew said, nudging the crow with his sneaker.

“Sure we can,” Jennie said. “It’s really easy. Here, watch this.” She started walking away, hands in pockets. “Easy!” she called back to us.

“Maybe we can put it in a shoebox,” I suggested, not wanting to abandon it, but also not wanting to do anything substantial about it, not wanting to take sides between the two of them.

Andrew pointed in my direction. Something like pride welled in me. “Yes! Good one, Caleb. Your donsaeng’s smarter than you, Jennie.”

“Show some respect for your elders, Andrew.”

He stuck his tongue out at her.

“We can use my shoebox,” Henry piped up, saying it in a rush, like he didn’t want to be left out. “I have it in my backpack.”

“Isn’t that for our class shoebox project?” I asked.

He shrugged. “I haven’t started it yet, so it’s empty. And I can always find another one at home.” Henry only owned one pair of shoes, so I wasn’t sure how he was going to do that, but let it go.

“Okay, let’s do this.” Andrew fist-bumped the both of us.

When Henry returned with the empty shoebox, he bent down and placed it next to the crow. The four of us stared at it, its black feathers not quite blending in with the black asphalt.

“So,” Jennie crossed her arms. “Before one of you idiots even thinks about touching this, you can’t use just your hands. God knows what kinds of things are on it.”

Andrew rolled his eyes. “Duh. We’re not dumb.”

Jennie blew the wisps of hair out of her eyes. “Are you gonna do it, then?”

Andrew shifted his weight from foot to foot, fidgeting with the hem of his t‑shirt. I realized, then, that Andrew was feeling something I thought he didn’t have: fear.

The next thing I knew, I took off my t‑shirt, feeling the sun against my bony, sticky, eleven-year-old back, wrapped my hands around the fabric, and picked up the crow.

“Caleb!” Jennie yelped, taking a step back as I held it by the tips of my fingers. I thought it would smell––don’t dead animals usually? especially in the heat?––but the crow emanated nothing.

Both Andrew and Henry gaped at me. I didn’t look at either of them as I placed the crow, gently, into Henry’s empty shoebox. When I did look up, at Andrew—hoping to see, I don’t know, admiration, maybe—he was looking elsewhere. In fact, Henry and Jennie, too, were looking in the same direction. At the same person.

It was David Moon, senior star of the high school soccer team, Ivy League bound, beloved of all ajummas at church. His car idled as he got out, walking, for some reason, toward us.

“What you guys got there?” David pushed his sunglasses to the top of his head. “And why’s your little brother got no shirt on, Jennie?”

“David?” Jennie’s voice squeaked. She coughed, clearing her throat. “Er—well—”

He looked at her, up and down, eyes lingering. We could all see her blushing. Then he turned to the three of us. “Is that a dead crow?”

“Andrew found it,” Henry said immediately, and Andrew glared at him.

“Cool,” David said, and Henry looked like he wished he hadn’t given Andrew credit. “Why’s it in a shoebox?”

I lifted a finger, as if to say it was me, but the words never came out. David noticed the movement, and he smirked—though not at me, at Jennie.

“Cool. Like your sister.”

Henry and Andrew both looked at me, as if to say, Jennie? Cool? But no one disagreed with David.

Jennie shrugged in response. “Not that cool.”

“What are you guys gonna do with it then?” David asked.

Henry shrugged. “Should we throw it out?”

“No,” Andrew and I both said. Jennie opened her mouth as if to agree with Henry, but closed it.

“Fine, fine, fine.” Henry pushed the box into David’s hands. “Do you have any ideas?”

He looked away, at Jennie, away again. “Yeah, I’ve got one, actually. I’ll take care of it for you guys.”

Andrew frowned, as if he couldn’t believe that David Moon, of all people, would be willing to take a dead crow from three eleven-year-old boys. “You sure?”

“Oh yeah,” he ruffled Andrew’s head, which might’ve made him mad had it been anyone else, but it was David Moon. “Your crow’s in trusted hands.”

“But what are you gonna do with it?” I asked.

He clapped my shoulder. “Don’t worry, little Park. We’ll leave it up to God, right?” He fist-bumped all of us before heading to his car.

At the driver’s side door, sunglasses back on his face, David turned back to us. “Hey, big Park, wanna help me with this?”

Jennie looked at me, at Henry and Andrew, back at David. “Me?”

“Yeah, you, Jennie.”

“But I—” she cleared her throat. “I have to babysit them. You know how our parents are …” she trailed off as David turned his gaze on us.

“You guys are gonna be in what, sixth grade soon?” he said. “Aren’t you old enough to look after yourselves?”

Both Andrew and Henry puffed up their chests; yes, they were, indeed, actually old enough to look after themselves—there were plenty of times when Jennie left us alone, after all. She was unwrapping and wrapping that drawing from earlier. I couldn’t see the whole thing, but there was a corner of a face, a boy’s face, I thought.

Jennie didn’t have any babysitting money on her yet to bribe us with letting her go. But Andrew didn’t care that we weren’t getting any money from Jennie, at least not this time. He nodded at David. “Yeah, duh, we are.”

“Alright, then it’s settled.” He opened the door. “Jen, you coming?”

No one ever called Jennie Jen. I frowned, but when she looked back at me, head tilted to the side—is this okay?—I waved at her. She fisted the paper back into her pocket and got into the passenger side of David Moon’s car.

~

Earlier today, Henry and I met at our local Paris Baguette for our once-a-year check-in. When we meet, it’s usually to catch up on the details of our lives any stranger could find on our Facebook profiles. It’s also to exchange any new information we have on our old friend Andrew, who’d slowly dropped out of our lives in the way friends do, after he moved away before we all started high school. Henry’s friends with him on Facebook, whereas I occasionally check his profile now and again, mostly to see if he has a new girlfriend or not. Usually, we leave after thirty minutes of chatting over mediocre coffee and red bean filled breads.

But this afternoon, after we asked each other how we were, if I still had a boyfriend (no), if Henry was still leading youth groups at our old church (yes), if I would ever go back to church (no), if Henry knew whether Andrew was still dating a white girl and whether his parents disapproved (yes), I was expecting us to shake hands and walk our separate ways, when Henry ordered a second cup of coffee. It was unheard of.

“Caleb,” he said, after returning to our table. “Did you hear about David Moon?”

I blinked. I hadn’t thought about David Moon since that day we found the dead crow. “No.”

“Well, you won’t believe this.” Henry leaned forward, so I did, too. He looked around, eyes flitting from face to face—probably trying to make sure he didn’t recognize anyone, and that no one recognized him. “There’s allegations against him. You know, sexual assault allegations.”

I blinked again, leaning back. “What?”

“Yeah. Sunmin Jeon, you know, the one who played piano for the church orchestra?”

I shook my head. I hadn’t been to church since junior year of high school, and even back then, I only ever talked to Henry. If Andrew had still been there, maybe I’d have talked to him too.

“Okay, well, she came back for the Class of 2010 Reunion, she was in the same grade as David, they were both in the church orchestra. But apparently she reacted pretty badly when she saw him, ’cause it’d been years—” Henry was now gesturing with his hands, “—and then people noticed and asked what was wrong, and she told them. It happened the first or second year in college, when they were back home for the summer and helping out with the orchestra.”

It felt like there was something stuck in my chest. “Shit,” I murmured. All I could think about was that image of Jennie getting into his car, playing on loop over and over again.

“Yeah. But that’s not even the whole thing.” Henry leaned in even more. I started to feel sick over the prospect of another woman—could it have been Jennie?—and it didn’t help that Henry seemed to enjoy telling me about these women as if it were just another piece of the latest Korean church gossip.

“The other day,” Henry continued. “After mass, I heard one of the ajummas talk to another ajumma about what a shame it was that David had hurt another girl. She was a little younger than Sunmin, maybe closer to your noona’s age?—” my leg started shaking under the table at the mention of my older sister “—and told some people a week or so after the reunion. Can you believe it?”

I could. Henry didn’t give me time to respond, though, before he leaned back in his chair, sighing. “David Moon. It’s too bad—I always thought he was one of the good guys.”

And what about the women? I wanted to ask him. Do you feel bad for them too? How are they doing now? But he probably didn’t have the answers, and even if he did, I wasn’t sure he’d tell me in a way that would stop my leg from shaking.

Instead, I asked, “Do you remember that day we found the dead crow?”

~

Hours after I met with Henry, I get ahold of Jennie.

“Caleb,” she answers on the fourth ring. “What’s up? I thought we weren’t gonna talk until later?” Jennie lives in California, working on graphic design for some media company, while I’m still in New Jersey finishing up college, and we call each other exactly on the fifteenth of each month.

“Hi, noona,” I reply, wishing we still used old analog phones so I could fidget with the cord. Instead, I keep tapping my fingers on my knee. “There’s something I need to ask you about.”

“What is it?” There’s some sort of background noise on her end—is she stuck in L.A. traffic? Eating at the food court in Koreatown?

I take a breath, curling my fingers into a fist. “I talked to Henry the other day. He—he told me something about David Moon.”

Silence on the other end.

“He, uh … at church … there are two women …” I stammer. Clear my throat. I start over. “I keep thinking about that day we found the dead crow. Do you remember?”

“I remember,” Jennie’s voice, though I can barely hear it.

“Did … did something—” I cough. “Did something—”

I can’t finish my question, but Jennie’s silence gives me the answer.

~

While Jennie was sitting shotgun in David Moon’s car, going who knows where, Andrew, Henry, and I returned to Andrew’s. The power was still out, so we found ourselves lying on the hardwood floors again, splayed out as far as we could, hoping they could cool us down.

“What do we do now?” Henry asked.

My eyes were on the ceiling, but I could almost feel Andrew’s shrug from across the room. “Wait until the power comes back.”

“But that could be hours.”

“You got any better ideas?”

Instead of listening to them argue—or until their argument could reach me, and I’d have to be the one responsible for coming up with something fun to do—I got up and walked to Andrew’s parents’ room, where Jennie had been sitting in front of the desktop computer, sketching something.

I sat down in the chair, imagining her here. Scrolling through Myspace or Facebook and talking to her friends, probably complaining about us. What were she and David Moon doing together now? What was happening to the crow?

Next to the keyboard was Jennie’s sketchbook. It was closed, and my fingers hovered over the cover, hesitant. DON’T TOUCH ANY OF MY STUFF Jennie would often say to me. I could imagine her ripping the sketchbook from my hands as soon as I touched it; but Jennie wasn’t here right now, to watch as I opened the sketchbook, flipping from one drawing to the next.

There were a bunch of portraits of her friends at school, in the cafeteria, in class. One or two of David. One of Andrew, Henry, and I with the GameCube. One of our parents. None of herself. In the middle of the sketchpad was a torn-off page, hastily ripped on the side.

I touched the edges, careful not to give myself a papercut. Was this the drawing Jennie had in her pocket?

I heard footsteps in the hallway and quickly closed the sketchbook, turning around to find Andrew in the doorway.

“Your omma’s here,” he said, simply, then walked away.

When I got home that night and went to my bedroom, the one I shared with Jennie—hoping to give back her sketchbook without her discovering that I’d looked through it—I found her lying on her bed, her back facing me.

“Noona?” I asked, quietly.

She didn’t say anything; I tried again, then a second, and then a third time. After the third time, I figured she was asleep, and that’s when I noticed the drawings on the wall on her side of the room.

They were all crows. Doodles, sketches, scribbles. Tiny ones, big ones, medium-sized. Varying shades of black and gray. If I looked away, I swore I thought I saw their wings flap out of the corner of my eye. It couldn’t have been a breeze, because the window was closed. But when I looked at them head-on, they were still.

~

“Where do I even start?” Jennie asks, exhaling. I don’t hear any background noises on her end of the phone anymore—she must’ve found somewhere quiet to talk.

“What do you remember?” I whisper, my voice so quiet I’m afraid she hasn’t heard me—but Jennie starts talking.

“The power went out that day. Do you remember that?” I nod, though she can’t see me. “I was messaging David on AIM, asking him for help with geometry homework, ’cause he was one of the tutors my teacher put on a list, and I thought he was cute and liked watching him play soccer, so I thought, I don’t know, why the hell not?”

She says everything in a rush. My leg keeps shaking up and down, waiting for the moment her story turns.

“I told him I was babysitting you and Andrew and Henry, then he asked for Andrew’s address, I gave it to him, the power went out. I didn’t actually expect him to show up. I really didn’t. David Moon, a senior, and me, a freshman? God, everyone was in love with him.”

“You had a crush on him,” I say, a statement more than a question.

Jennie exhales again, a bit shakily this time. “I did. I thought he was––I don’t know. But then, who would’ve believed me, right? He asked me to come with him, when he took that dead crow for us. And I said yes. I said yes, thinking we’d just work on geometry after. And, you know—part of me—” she pauses, takes a breath, starts again. “Part of me, I know, was hoping for something. A kiss, maybe. Something small. But not that. Not what happened.”

My hand is curled into a fist, fingernails digging into skin. If only I had—what? Asked Jennie not to get into the car with David? Followed them, impossibly? Asked why she was spending longer times in the bathroom after that day?

“Caleb? Are you still there?” Jennie asks.

I close my eyes. “Still here. Sorry. Just—a lot to process. There’s so much I didn’t know, or didn’t remember, but thinking back on everything now, it—it—some of it—”

“Is starting to make sense?” she finishes. “You were eleven, Caleb. I was your annoying noona. You were my insufferable donsaeng.”

“I’m still your insufferable donsaeng.”

She laughs, but it comes out garbled. “Then I guess I’m still your annoying noona.” A pause. Seconds of silence pass. “You know—I’ve never actually really told anyone what happened next. I think a lot of people thought I was a prude ’cause I didn’t have my first boyfriend until after college, but … well––” Another breath. I wish I was there, in Los Angeles, to put my hand on her shoulder, or give her a tissue, anything. But there’s a part of me that’s glad I’m not, so I don’t have to see her face crumple when she starts talking again.

“He took me to the church parking lot,” she says. I can see it in my mind so clearly, years later: the main lot, with its clean white lines. And several hundred feet away, in a spot overrun with grass: the place of my first kiss. I’d snuck off at night to meet up with another closeted guy from a different high school. We thought we were being hilariously ironic, transgressive. But this was a different place for Jennie.

“None of the ajummas or ajusshis knew about that spot, you know. So he knew there was no way anyone would see us.” She takes another breath. “So—yeah. That’s it. I don’t—I don’t want to get into the details.”

“I don’t need to know them,” I say, hoping it’s enough.

There’s a sound on the other end, like she’s blowing her nose. “I thought we were gonna bury the crow in the trees behind the parking lot. But he started kissing me—which, you know, I thought I wanted, but then—it didn’t stop there. Even though I wanted it to. To stop, I mean.”

What do you say to your older sister who’s just told you a terrible secret? What do you do when she’s reliving the trauma, when that day for you meant finding a dead crow and trying to impress your friend you had a crush on and for her meant something completely, utterly different?

“God,” she laughs, or cries, I can’t tell which. “It’s just so—I’ve spent so long replaying this day in my head. And now I’m finally telling someone.”

“You don’t have to keep going,” I say, gently.

“No, I—” she stops. “God, Caleb. What if I’d told someone earlier? You think the same thing wouldn’t have happened to those girls?”

I’m about to answer, when she continues in a rush of words.

“There’s one part of me that says, You couldn’t have known. No one would’ve believed you anyways. And then there’s the side that says, What if they did? What if one of them did? And then the other side says, Look how they’re reacting to them now. All the ajusshis and ajummas can talk about is David this, David that, how he was so successful and now it’s all collapsing. They would’ve done the same to you ten years ago. They wouldn’t have cared about you. They would’ve told you to keep quiet because no one can know that something terrible like this happened to us, us upstanding church-going God-loving Koreans. But then, what if one of the girls had heard about you, and decided to stay away? What if it made all that difference? And then I come back with—but it shouldn’t have rested on them, on us. It should’ve been on David.”

There are half-moon circles imprinted on my palm from where I’ve been digging my nails into the skin. “You can’t blame it on yourself.”

“I know I can’t.” She laughs. “I know. I fucking know. But I spiral sometimes, Caleb, I spiral. But you know what some of the weirdest, creepiest shit out of all of this was?”

“No.”

“I don’t know what he ever did with the crow, but when I got home, I couldn’t stop drawing them.”

I blink, remembering the crows on the wall. “But you hate birds.”

“I do. But when I picked up my pencil, it was like my hand took over me. I think I went through an entire notebook. And then at school the next day, when David Moon opened his locker, a bunch of post-it notes flooded out.”

My mouth hangs open. “Did you—”

“No, I didn’t even go near his locker that day. But I sure as hell hope he got a ton of paper cuts.”

Witnesses, I think. But I don’t say this out loud to Jennie. She might’ve been silenced, but they were trying to say something.

“When I got home,” Jennie continues, disrupting my thoughts, “all my drawings of the crows from last night were gone. All that was left was the tape on the walls.”

Chills run down my arm. “Sounds like one of omma’s superstitions.”

Jennie laughs. “I know.”

When we get off the phone, I lie down in my bed, staring up at the ceiling. Through the closed door, I hear one of my housemates come in, rummaging through the pots and pans in the kitchen. For him, it’s a normal day: classes, work, student org stuff. For me, I can’t stop thinking. Can’t stop the images swirling behind my closed eyes, dead crows and silence and Andrew and Henry and David and Jennie and that hot June day that used to mean something different for me but now—now moves beyond that dead crow I picked up with my t‑shirt, sun beating down on my bare skin and wondering what would happen next.

From the writer

:: Account ::

“What the Crow Knows” began as an inquiry into a memory.

When I was in third grade, my friends and I found a dead bird on the side of the road. Unsure of what to do, my friends’ older siblings took charge—I remember there being a shoebox, a strange man who approached the siblings, and I remember myself, my cousin, and my friend going back to his house and distracting ourselves by watching TV. I remember being vaguely worried about the older siblings, but in the end they returned just fine, the dead bird having been taken care of.

Part of this inquiry is a “what if”—what if this stranger wasn’t a stranger but an acquaintance of a motley crew of kids? What if the older siblings—just one older sibling in the story, Jennie—doesn’t turn out fine? What if the younger kids, who might not be fully aware of the underlying power dynamics between those older than them, remember this day differently than them?

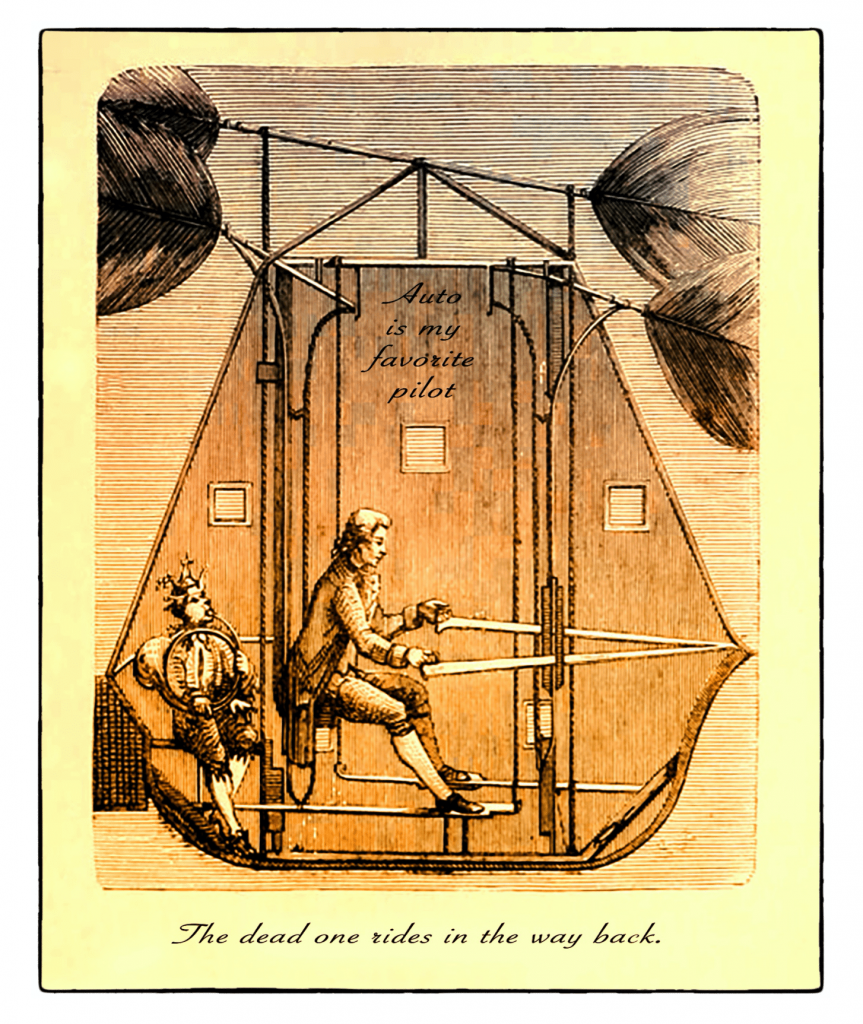

Part of this inquiry is also ruminating on what happens when we realize more sinister things had happened retroactively, and when our memories of a certain day or event don’t match up with the memories of someone else. It is also about, of course, confronting sexual assault and trauma, and the lingering consequences of trauma of that assault and abuse––on the survivor, on the survivor’s family, on the survivor’s community; and what that means for a specific cultural community. Part of that confrontation asks––what if there is no witness? What if the only witness is a dead crow?

Monica Kim is a queer writer and organizer. Born in Korea, she now lives in Brooklyn, New York. She won the inaugural Jane Kenyon Chapbook Prize Award for her series of multiverse poems and her writing has been published in the lickety~split, Pollux Journal, Pine Hills Review, and others. You can find her on Twitter at @kimmonjoo.