Fiction / Christine Seifert

:: The Last Rhubarb ::

Heather arrives just before seven. She peeks into the tent where I am adjusting the antenna on the old TV from Gary’s room. If he were home, instead of at his new dishwashing job, he’d never let me borrow it.

“Neat,” Heather says. She uses the toe of her right foot, clad in a dirty white sneaker, a Keds knock-off that her mother bought her at the beginning of summer, to poke at the boxy TV. “Where’s it plugged in?”

“Garage,” I say. “It took two extension cords.”

“Where’s Gary?” Heather asks. She uses both hands to fluff out her hair. “Should we invite him out here?”

“Gross,” I say. The flicker of disappointment on Heather’s face comes and goes so fast that I almost miss it. But I don’t. I try to imagine Gary as a person other than my brother. Would I too have a crush on him?

We eat Cool Ranch Doritos while we watch Beverly Hills, 90210. “I’m such a Kelly,” I say during a commercial.

“You totally are,” Heather says. “I’m more of a Brenda.”

Neither of us are either of them. We are us. Knobby-kneed with mild acne. Dry hair with chlorine damage. Long feet, pointy shoulder blades, concave stomachs, tan lines. We are girls of summer. We are too young for jobs, but we are old enough to sleep in a tent in my backyard. To watch TV outdoors with a bag of Doritos and two cold Cokes.

After the show, we bring the cordless phone out to the tent, and it’s just close enough to the house to work. We call Todd first. Heather dials *67 to block caller ID. “Who do you like-like?” Heather asks in a low voice. She has a faded yellow pillowcase placed over the phone receiver, a sure method, she claims, to disguise her voice. “This is a friend,” she insists to Todd. “I just want to know who you like.”

“Damn,” she says to me. “He hung up.”

“Call again,” I urge her.

She shakes her head. “Let’s call Brad Stockton and ask him if he really did it with Tracey Lauren.” I flip open the worn phone book. “He’s unlisted,” I tell her and throw the slim book on Heather’s lap.

“Hot damn,” Heather says.

She’s taken to saying that this summer. Hot damn. It works for everything.

We open the phone book and dial whatever number we see first. We leave Dorito stains on the flimsy pages. We ask strangers if a Mr. Dong is available. Everyone hangs up on us except an old woman who tells us to quit playing with the phone or she’ll call the police and have us taken to the jail in a paddy wagon. I laugh so hard I almost pee my pants. Instead, Heather and I go behind the garage and pee on the rhubarb. “This stuff is poison,” I tell Heather about the plants. “If you eat the leaves, you’ll die.”

“Why would you eat the leaves?” she asks.

“If I were going to kill someone,” I tell her, “I’d sit on them and force rhubarb leaves down their throat.”

“Not me. I’d get the person to walk across the street with me and go on the path by the river. Then I’d tell them there was something on the river bank, something they had to see. Then I’d push them in.”

“What if they could swim?” I asked. “Everyone over the age of five can swim. They would just climb out.”

“They couldn’t swim if they were, like, high on rhubarb leaves.” It was a good point. “Also,” Heather adds, “I can’t swim.”

“Well, I hope nobody pushes you in the river.”

“Why would anybody push me in the river?” she asks and strikes a pose. “I’m too cute to die young.”

In the tent, we call strangers. Mostly they hang up. One guy talks a lot. Heather keeps asking him questions. They talk about cassettes and how lame New Kids on the Block are and how people in high school are so bogus. Heather whispers to him with her back to me, and I can’t hear what she’s saying for a long time. I strain and make out words: Come. Over. Soon. I grab the phone from her and hang up. “He can’t come over. My parents will freak. And you don’t know if this guy is old.”

“He sounds young,” she says.

“He sounds thirty.”

Heather grabs for the phone, but I quickly dial my own number so she can’t hit re-dial. I hang up when I hear the busy signal.

“Fine,” she shrugs. “Let’s do something else.” And so we go inside and get my yearbook and draw mustaches on all the girls we don’t like and poke pin-holes in the eyes of the boys we like but don’t want to like .

At eleven my dad comes outside and tells us to be quiet for god’s sake. And my mom comes out behind him and tells us to come inside if it rains or if we get scared. She says they will lock the door, but use the key if we need to get inside. The key is on a green stretchy bracelet around my wrist.

“My parents never lock their doors,” Heather tells my mom.

“Well, we do.”

“My mom is paranoid,” I tell Heather after my parents go back inside the house. “She always thinks someone is going to murder us in our sleep.”

“Is it better to be murdered while you are awake?”

It’s a good question. I make a point to ask my mother, in the same tone Heather used, next time she yells at one of us for forgetting to close our windows at night.

Heather does my hair in a French braid. I plug in rollers using the extension cord from the TV. “You could be in a pageant,” I tell Heather when I’m done. She is prettier than I am, but she has only recently figured it out. She doesn’t hold it against me, nor I her. It’s just a fact.

At quarter to one, Heather suggests we get dressed and walk to Village Inn to say hi to Gary. “We can get pie.”

Then we get into an argument because I don’t want to go. I don’t want to walk the five blocks. I don’t want to get in trouble if I get caught. I don’t want to see Gary. I don’t want to be murdered. Mostly, I don’t want my best friend in the whole world to have a crush on my brother.

I am too young to explain what it is I feel for Heather. It’s not romantic, but it’s a cousin to romance. It’s a feeling endemic to being thirteen and being a girl and having a best friend. I don’t want to kiss her or touch her, but what I do want is to feel so close to her that I will never feel alone again. What happens to me will happen to her. We’ll be connected to each other always, like twins in a womb. We will be so similar that when we die, they will have to identify us by our moles, our scars.

Heather gets mad and refuses to talk to me. But she won’t go without me. I know that. I listen to a George Michael cassette on my Walkman and cry softly. Finally, Heather softens. She scoots her sleeping bag closer and snuggles next to me. “Did you know that rhubarb is another word for a fight?” Heather whispers to me.

I don’t answer.

“We had a rhubarb, you and me,” she says.

I feign sleep.

“I’m sorry,” she whispers.

I don’t forgive her, but then I do. We sleep butt-to-butt, and I pretend it will always be like this.

It’s light outside when I wake up again. My dad is outside the tent. “Steffy, open up,” my dad is saying. I rub my eyes and unzip the flap. “Heather’s dad is here to pick her up.” My dad’s face is red and puffy. He’s wearing an undershirt and grey sweatpants. My mom will not come outside without her makeup, without having first rolled her hair around hot rollers. “Didn’t you hear us calling?”

I roll over and throw an arm on the sleeping bag next to me. It’s empty. “Where is Heather?” I ask.

~

I spend hours in the police station. They let me rest. They give me hot chocolate even though it is blazing hot outside. They buy Funyuns from the vending machine for my snack. They let my mom in the interview room with me. Then they send her out, and she protests, but she gives up because the detectives are very reassuring. I am not being blamed, they say. I am not being accused of anything, they say. They just have questions.

They ask me if Heather had a boyfriend. I tell them no, but I know she kissed Matt Vanyo at the top of the covered slide at Lyndon Street Elementary just last week. He put his tongue in her mouth and she described it as a big fat hairy caterpillar.

They ask me what happened to Heather that night. And I start to cry. They pat me on the back and call me sweetheart. “I can’t remember,” I say. And I can’t. It all runs together, a massive blob of colors, words, and movements that cannot be separated into discrete pieces. The blob is unblobbable.

They finally send me home to sleep, and I come back early the next morning. I still haven’t showered since before that night. My hair is matted and my eyes feel crusty. The detectives tell me to relax and to think carefully. Did I miss anything? Did I forget anything?

I start from the beginning of the night when I brought the TV outside. I tell them what happened on Beverly Hills, 90210, about Brandon at the beach club and Kelly and Dylan getting together behind Brenda’s back while she is in Paris with Donna. I tell them about the prank phone calls and about the chips, the French braids, the rhubarb we had over Gary. My parents sit on either side of me. My mom cries and sniffles loudly.

“Were you very angry?” one of the detectives asks me. He is tall and thin with bushy dark hair and a skinny mustache.

“I was very sad,” I tell him.

The detective with the mustache pats my forearm. “Don’t worry. You’ll remember more later. I promise. It’ll come back to you. It always does.”

When I sleep, I dream about the rhubarb patch.

~

School starts in September. I am not allowed to walk by myself, so my dad drops me off at the door, even though the school is only three blocks from home. “Gary will pick you up,” he tells me. “Don’t walk home.”

There’s a kidnapper on the loose, but the posters with Heather’s face are already starting to fade and fray. I think they should be refreshed, reprinted on clean white paper. I am somewhat famous because I was the last one to see her. Reporters call our house. My picture is shown on the news and my mom is horrified. “What if he comes back for Steffy?” she hisses at my dad when she thinks I’m out of earshot.

I think that being Heather’s best friend will make the first day of eighth grade easier. It does not. Nobody talks to me. Nobody even comes near me. It’s as if I’m tainted. I carry all their fear and mine inside my Esprit shoulder bag, my GUESS jeans, my Benneton crew-neck t‑shirt. It’s also inside me, mingling with my guts and my bones. Nobody wants to breathe it in when I exhale.

I am falling asleep in Geography, halfway between conscious and not, and it happens: I am no longer in a stale classroom surrounded by people who do not know me. I am back in the tent. It’s that night. I am there. Heather is there. A rush of love, warm and pleasant, sweeps over me. It’s like a breeze on the first sunny day of the year, when you hold your face up to sun and exhale. You won’t remember winter for much longer.

When I open my eyes, I am on the dusty floor. Mr. Griffin is standing over me. “Martin,” he calls, “you get the nurse. Shelby, you go get Mrs. Adamson.”

“Ew,” someone whispers, “I think she peed her pants.”

~

I stay home from school for weeks. I do none of the work Mrs. Adamson arranges to have sent to me each week. Sometimes Gary brings it to me. Sometimes Mrs. Adamson herself comes to the door, and when she does, I pretend to be sleeping. During the day, I watch TV for hours. I’m watching a re-run of Alice when it happens again. One minute Mel is verbally abusing Vera, who is so willfully stupid that it’s hard to side with her, then the next minute I’m back in the tent. My mosquito bites itch. Sweat drips from my hairline. Dorito dust coats my fingertips. I can smell Cool Ranch.

“Are you here?” I ask Heather.

“Of course. Where else would I be?”

“Are you going to see Gary?”

“Gary?” Heather scoffs. “Why would I want to see Gary?” She pulls out a deck of cards. “I have tarot cards,” she says.

“Will we stay here all night?” I ask her. “Can we stay in this tent?”

“Of course,” she says. “Don’t be a ding-bat.”

~

I go back to school after Christmas break, and I join the jazz band. I am third-chair flute, along with eleven other third-string flutists who do not know how to play well. We blow hard and chirp like a flock of chaotic birds. Mr. Douglas is patient and tells us to regulate our air.

In the coatroom after class, I am putting my flute case back in my cubby hole, safe for tomorrow, when it happens. Nobody is near me, so I let myself sink down on the floor on a pile of soft downy coats.

In the tent, I am awake and Heather is asleep. I watch her. She breathes in and out in syncopated jazz rhythms. She purses her lips on the exhale. I find myself mirroring her movements. She opens her eyes. “Why are you being a total spaz?” she asks.

“I need to know what’s going to happen tonight,” I say.

Heather sits up and scratches her head. Her braid is half-undone and strands of hair stick up like a crown of thorns. “Did you hear that?” she asks.

I strain, but I hear nothing. “It’s a boy,” she says. “There’s a boy out there.” She points to the flap of the tent. We sit still for so long I worry we will freeze like that and never move again.

And then he is in the tent. “How did he get in—” I start, but Heather cuts me off. She gets on her knees. The tent is too short for her to stand. The boy is kneeling, too.

“Have you come for us?” Heather asks.

“If you would like to go with me,” the boy says. His cheeks are pink. His hair is thick and combed into a style from ages ago. Slicked back on the sides. Floofy in the front. Kind of like Brandon’s on 90210. He is our age, I think. Maybe older. Maybe much older.

Heather says, “He wants us to go with him.”

“Where?” I ask. I am scrambling for my shoes because I already assume she will assent, and I can’t let her out of my sight.

“Just me,” she says. “You have to stay here.”

“I won’t let you go alone.”

“You don’t have a choice.”

~

They correct me when I call it a hospital, but that is what it is. I’m here for a rest, my mom tells me. I sleep and wake, wake and sleep, for what feels like forever but is really only a week or two. Then I’m back at home. Our priest, Father Hanson, comes to visit me. He asks me to say a rosary with him, so I do, but I’d rather watch TV. Father Hanson tells me God has a plan. It will all work out according to the plan. “Why would God want Heather to be kidnapped?” I ask. Father Hanson doesn’t answer; instead, he tells me to pray. He gives me the words to say, and I know that there are other words I can never say. I remember that I’ve only ever seen him without his collar once. He’s wearing it now. Without it, he looks like someone who looks like someone I know.

I go back to school, but I’m too far behind in band to play. Instead, I sit outside the door with my knees tucked up under my chin and listen for the third chairs. The din rises above the real notes and it’s kind of beautiful, the way they are all doing something different together.

After school, I go to counseling. Gary drives me and waits outside. He smokes in the car, and I worry that the therapist will think it’s me. She never asks about it. Maybe she assumes that anyone who comes to counseling is also a smoker.

Her name is Judy and she wears large painted necklaces made out of wood and broomstick skirts. Her hair is very short, and she runs her fingers through the front three times per every five minutes. “You don’t have to talk about Heather,” she tells me on my third visit. “That seems hard for you. Let’s talk about your parents instead.”

I tell her my mom makes delicious potato salad and likes to play tennis on weekends. She falls asleep when she watches TV, and she stays up late to read news magazines and drink Mr. Pibb. I tell Judy my dad is loud and loves to argue. He puts together model planes for fun. He is an engineer and reads books about bridges. He met my mother on a double-date, but she was not his date. The other girl, my father’s date, was the maid of honor in their wedding. She died of cancer when she was only twenty-six, and my mom lights a candle on the anniversary of her death every year. My parents believe in God and the Catholic Church. By extension, so do I.

Judy nods and writes notes on a small notepad in green ink. “I see,” she says. She pauses occasionally to look through half-track glasses that she keeps on a red string around her neck. I worry that her large wooden earrings will tear through her lobes and leave a bloody mess like the bottom of a package of raw hamburger.

“Breathe in,” Judy tells me. I do.

“Breathe out,” she orders. I do.

On the way home, in Gary’s car, the window rolled down, I inhale his smoke until my lungs are full. Then I let it out the window and pretend that I am smoking too. Gary plays a Metallica tape and my ears throb. It doesn’t take long for me to disappear.

In the tent, Heather is talking to the boy. The man. “I feel like I know you,” she says.

“I have that effect on people,” he responds.

“Who are you? Where did you come from?” I say.

The boy sits down and crosses his legs like the statue of Buddha I saw in my World History textbook. He breathes slowly. Inhale. Exhale. “It doesn’t matter who I am. I’m here for Heather.”

“I don’t want her to go,” I say.

“Steffy, don’t be a baby,” Heather says. “It’s not like I’m picking him over you. This is, like, a separate thing. Separate from us, you know?”

I didn’t know. “Do you even know him?”

“I don’t have to know him,” Heather says. “The point is that he’s come for me.”

The boy smiles. He reminds me of the glowing figures in the stained-glass windows, the cherub faces that are not human but aren’t inhuman either. “How old are you?” I ask.

The boy laughs. He has grooves in his forehead, crinkles at his eyes. He is not glowing so much as he is radiating something, something that feels hot and insistent and permanent.

~

After supper one night, when I’m already in my pajamas with my teeth brushed and flossed, my mom and dad come to my room and sit on the edge of my bed. Gary hovers in the doorway. It is almost a year since Heather vanished.

I yell for my parents. “I know what happened to Heather!” I shout. The story appeared to me. Not in a dream. Not like a film. But like a thing that I always knew, like the color of my mother’s eyes and the smell of my sheets.

“What? What have you remembered?” my dad asks. He shushes my mom who has gasped, who has begun to cry.

“You’ve remembered?” my mom says. She grabs the cordless phone from my bedside table. “I’m calling the police.”

My dad takes off his glasses and rubs his eyes. He motions for my mom to sit. She sets the phone back in its cradle. “Why don’t you tell us, sweetheart, before we involve the police,” he says, and I already know he doesn’t believe.

I tell them everything, including the bits that don’t matter. I piece it all together, patchworks of memories that have come back when I let them. I tell them about all the times I’ve gone away and come back with a new old memory.

“Who is this boy?” my mom interrupts. “We have to find him. We have to call the police.”

“Sharon,” my dad says, “let her finish.” He pats my leg, “Go ahead, Steffy. Finish the story. We’re listening.”

“He came to us. He was inside the tent with us. He was sent for Heather. He said just her. Not me. She was the one who was meant to go.”

My mom is crying so hard that Gary must step into the room and prop her up. She is a scarecrow. He is a post.

“Then they exited the tent together?”

“No, they didn’t exit. They disappeared.”

“What does that even mean?” my dad asks.

Now I am annoyed because I know this story and now they are ruining it with their questions. “It means, one second they are there, the next they are not. I am alone in the tent.”

“Poof,” my dad says.

“Exactly. Poof. Gone. Now you are getting it.”

“That’s not possible.”

I shrug. “The boy, the man, said it is all possible. Everything is.”

“But I don’t understand,” my mother says. “Why didn’t you come get us? Why didn’t you scream? Why didn’t you tell the police? And who is this man? What did he look like?”

“What does God look like?” I ask her. “You can’t say. It’s the same thing. I can’t say.”

My mother falls to her knees and wails. My dad tells her to stop. He tells Gary to take her to the kitchen, to leave us be for a minute or two. When they are gone, he picks up one of my hands. His palm is clammy, but mine is soft and dry. “Steffy, how do you feel? You can be honest with me. I can help you. We can all help you.”

“I don’t know. It was her time. It was meant to be. It was part of the plan. God will never give you more than you can handle.” My cadence sounds familiar. I sound like Father Hanson mid-sermon. I think about the times Father Hanson picked me to help him in the rectory. He picked me more than any other girl. I paid attention. I thought about my hands in soapy water in the rectory sink, washing dessert plates, and listening to Father Hanson tell me all the things God wants for me. I never told him that when I was five, I thought he was God and I was happy that God lived in my church, not anyone else’s.

My mom returns with a cup of water in her hand, and I’m not sure if it’s meant for her or me. “He had pale skin, yellow hair, red cheeks. He glowed, like a lightning bug. He was human but not.”

“Oh, my poor baby,” my mother whispers.

“What do you mean?” my father asks.

“He came to take Heather. And then they disappeared.” I snap my fingers to demonstrate how fast it was.

“Steffy,” my father says, “people don’t just disappear like that. They don’t get taken from tents by men who are like God but not God. That’s just not reality.

I shrug. “He works in mysterious ways.”

“The man or God?” Gary asks, and now I’m starting to feel confused.

“But this man,” my father persists. “Who is the man?”

“I told you. He takes the form of a human, but he is from the spirit world—or whatever. I suppose you might call him an angel, but he didn’t really say. It was Heather’s time to go, and he took her to be in a better place. She is where she’s meant to be, so we should all be happy for her. She’s been called home.” I feel relieved now. It’s all so clear, like the surface of glass tabletop, that I marvel there was ever a time when I could not say these words, the words the man himself told me. And only now does it all make sense. It all fits together perfectly. I lay back and smile, for perhaps the first time since Heather left this world.

“Oh, my baby,” my mother says again. She is shaking and sobbing and Gary is back trying to pull her off of me. “None of this makes sense,” my father says, “it’s simply not logical.”

“Heather floated up, up, up. Out of the tent, up in the air. She dissipated. Like smoke. I could see it all through the canvas. We can tell the police to stop looking,” I say. “If she comes back, it will be because the man brings her back from the sky. When it is time.” I smile at the three of them: Mom and Dad and Gary. See? I’m trying to say. It all works out.

“She’s crazy,” Gary says, as if I cannot hear him. “She’s pure batshit.”

“That can’t happen,” my dad says again. “It just can’t.”

“Why?” I ask, marveling at all he doesn’t know yet.

“Because the universe has rules!” my father shouts at me. For one brief moment, he looks at me as if I am someone else. Then he is holding both of my hands. “I’m sorry, Steffy. I’m sorry I yelled.” I giggle because his cheeks are too red, his hair messed up, his glasses crooked.

My father stands up. “I’ll call the doctor,” he tells my mother.

I find myself drifting into sleep, deep and restful. God gives. God takes away.

From the writer

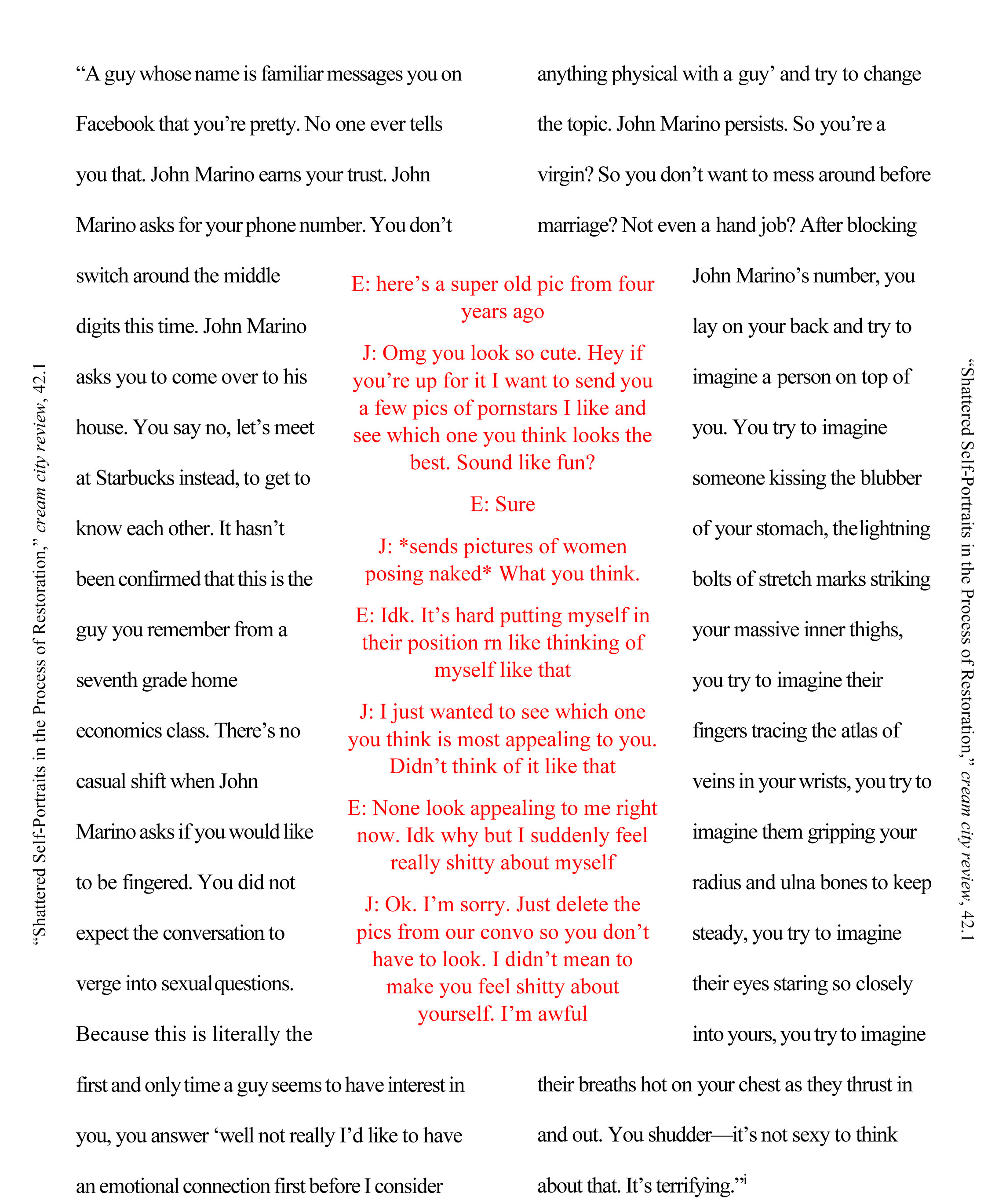

:: Account ::

History

I am originally from Fargo, North Dakota, which is probably why I gravitate toward dark and cold stories set in the upper midwest. I love characters who are torn by what they want and what they *ought* to want. I’m intrigued by characters who surprise me, who confuse or repel me, and who underestimate the ripple effect of any one decision (or indecision). I like stories that hint at the outlandish and the other-worldly, but also demonstrate the terror of reality. I want readers to decide what’s worse: the realm of the supernatural or the Tuesday we’re living right now.

Sketch

In this story, the main character, Steffy, is traumatized after her best friend disappears while camping in their backyard. As the community searches for the missing girl, Steffy experiences flashbacks to that night. Does she know what really happened? Or is her memory of Heather’s disappearance colored by a previous trauma, one that is buried below a glossy surface?

Marker

All of my work gravitates around one idea persistent question: Are we ever in control of our own lives? What if it’s all a sham, I wonder. Maybe that’s the point of literature—or any kind of art: We all want to pretend we’re in control of something. Steffy thinks she’s in control of her own memories. And yet nobody believes that she has a grasp on reality. After all, she seems to think Heather has been kidnapped by God.

Repository of Influences

Like many writers, and probably like you, I’m a voracious reader. I’m cynical and irreverent and curious and confused and doubtful. The stories I love most are the ones that strike those chords and rattle my brain. I will never forget the line of sweat, the hair dye, running down Arnold Friend’s face in Joyce Carol Oates’ story “Where Are You Going, Where Have you Been?” as Connie realizes what she’s just done, the way she’s sealed her own fate. Steffy is an homage to Connie, but her Arnold Friend is hidden in the depths of her own mind.

Christine Seifert is the author of one novel published in three languages: The Predicteds (2011); two nonfiction books for young readers: Whoppers: History’s Most Outrageous Lies and Liars (2015) and The Factory Girls: A Kaleidoscopic Account of the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory (2017); and one academic book: Virginity in Young Adult Literature after Twilight (2015.) She’s also written for The Atavist, Bitch Magazine, and Inside Higher Ed, among other publications. Born and raised in Fargo, North Dakota, Christine is now a Professor of Communication at Westminster College in Salt Lake City, Utah, where winter lasts a reasonable period of time.